Writing is a difficult pursuit. Just this week I found myself struggling with characterisation. When I tweaked the characters, the plot went with it and I felt like I was patching up a leaking ship. You may think that there are big problems if you’re needing to “repair” your story, but in my case I improved upon the way the plot was working and ended up with something far stronger than I had to begin with. Not every leaking boat sinks.

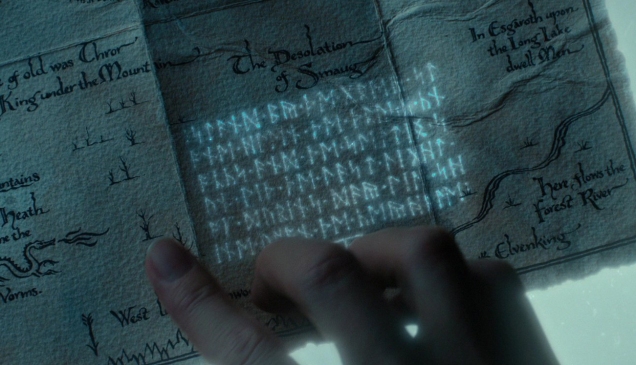

After I’d sorted out the annoyances with my story, I looked to the setting. I always spend a very long time worldbuilding and getting the various locations clear in my head. I try to treat it like a movie. There are various “sets” and each one is designed for a specific purpose, whether its to evoke a certain emotion in the reader, to act as the backdrop for a major event or simply to help make the world feel more real and add flavour. If you’ve seen any of the Lord of the Rings movies, surely you remember Amon Hen, the place where Boromir is killed defending the hobbits? How about Helm’s Deep or Minas Tirith? Surely you felt disgust when Isengard’s gardens were destroyed and transformed into evil pits? These scenes invoke very specific emotions and the sets are designed to heighten the drama that is taking place within them and cement the story very firmly in a living, breathing world.

Just read this short scene and see if you can visualise where it’s taking place:

‘I’m not sure,’ Jeremy said. He set his flask of tea down. ‘It’s a sticky situation.’

Thomas hauled himself from the sofa and went over to his desk. He opened a drawer and produced a book. ‘This here is all we need to bring them down, Jeremy. One pathetic man and woman at a time.’

Jeremy stared out of the window. ‘Fine,’ he said. ‘Do it.’

Can you picture where that conversation is taking place? Do you know how big the room is, where in the room the desk is or what the book looks like? Do you remember what Jeremy is drinking tea from? When you come across writing like this, it’s being made unnecessarily difficult to picture everything.

Have a read of the same scene below but with some description of the setting included:

‘I’m not sure,’ Jeremy said. He set his flask of tea down, its weight suddenly dragging at his frail muscles. ‘It’s a sticky situation.’

Thomas hauled himself from the leather sofa that looked better suited to an executive office and crossed over to his mahogany desk in the corner. He opened the top drawer, remembering it was quite stiff and produced a dusty, leather bound-book. ‘This here is all we need to bring them down, Jeremy. One pathetic man and woman at a time.’

Jeremy stared out of the misted window beside him. The wet London streets outside seemed like an alien world compared to the warm comforts of Thomas’ apartment suite. ‘Fine,’ he said. ‘Do it.’

Now, try and tell me that wasn’t easier and more interesting to read? Just from a few extra descriptions, we learn that Jeremy is either an older man or he is not very well and we remember the flask because it interacted with Jeremy in a meaningful way. We also learned that Thomas doesn’t have a very good eye for décor and the book he retrieves from his desk is old and has seen better days. Finally, we learn that this takes place in London and it is raining outside. Jeremy is a man used to comforts as he views the streets as alien. Now, the reader starts to piece a few more things together that you’ve not even started to hint at or explain. Best of all, they start asking questions and getting involved in the story. Perhaps they are politicians? Perhaps the book is a last resort and has been kept out of sight for years? Why does Jeremy have a flask of tea? Maybe he’s travelling somewhere and doesn’t intend to stay long?

You may think example two improved upon the first greatly, but there is still more we can do with this. The setting is clearer in our heads, but it’s not alive yet. This is where we come to my main point. To truly make a setting come to life you need to treat it like a character.

Let’s play around with that second example:

‘I’m not sure,’ Jeremy said. He set his lukewarm flask of tea down, its weight suddenly dragging at his frail muscles. The side table quivered unsteadily as it took the flask’s bulk and Jeremy knew it too had been worn down and abused over the years. He rested his withered hands in his lap and regarded his friend. ‘It’s a sticky situation.’

Thomas hauled himself from the leather sofa, the material making a sucking noise as his trousers pulled away. The thing would have looked better in some young executive’s office, surrounded by glass, slate tiles and minimalist art. Thomas crossed over to his old mahogany desk in the corner and opened the stiff top drawer to a cacophony of loud scraping noises. He reached inside and produced a dusty, leather-bound book, its cover faded and peeling away.

‘This here is all we need to bring them down, Jeremy,’ he said, holding the book aloft and shaking it excitedly. ‘One pathetic man and woman at a time.’

Jeremy stared out of the misted window beside him. The drenched London streets outside seemed like an alien world compared to the warm, inviting comforts of Thomas’ apartment suite. The aroma of freshly baked bread danced past his nose and his stomach immediately growled in protest. ‘Fine,’ he said, irritably. ‘Do it.’

By trying to really make the scene come alive, not only does the reader feel more involved but the word count has also more than doubled. If you find that your chapters never quite reach the length you want them to, take a look at your scene-setting and make sure you’re pulling out all the stops and inviting your reader in. Another outcome of making the setting more dynamic is that it makes your characters more three-dimensional and human. Notice that I also included more sensory description in that last example. The sound of the drawer opening, the sight of the book cover peeling away, the smell of the fresh bread and the feel of Jeremy’s hunger and impatience. It’s certainly a far cry from the first example.

By the way, this is a perfect exercise for you to try out if you’re struggling with describing a scene. Write a couple of really basic sentences and include a bit of dialogue. Then, expand on it and include basic, superficial descriptions like colour and size. Don’t be too specific or the reader won’t use their imagination for anything and then they’ll feel uninvolved. Once you have your improved scene down, really go for it and hit it with all you’ve got. Imagine you’re dipping a colourful paintbrush into a clear glass of water. See all the colours swirling together and colliding to make the water more interesting. That’s your goal as a writer. What would you choose, water or chocolate milkshake? A pond or the ocean? A goldfish or a lion? Get under the skin of your world and find out what makes it tick.

If you take nothing else away from this article, take this. Remember those old Disney cartoons from the 90’s where the background was like a painting and it never moved? When you saw one object drawn more vividly you knew it was going to move or do something. That’s what you want to avoid. To make a truly living world you need to make everything vivid and make the reader always guess what’s going to move and what isn’t.

Shake things up and make them fizzy!